The Mandelbrot nature of modularization

Benoit B. Mandelbrot referred to himself as a “fractalist” and is recognized for his contribution to the field of fractal geometry, which included coining the word “fractal”, as well as developing a theory of “roughness and self-similarity” in nature.

– en.wikipedia.org

In the world of software, modularization is crucial for maintaining flexibility, scalability, and code readability. I have participated in many discussions about the ideal size of a module. These discussions often feature extreme opinions, ranging from “it’s better to have a few large modules” to “the smaller the modules, the better”. The truth, as always, lies somewhere in between, and in this post, I will point out how to pinpoint it.

What is a module?

In the world of software engineering, a module does not have a clear-cut definition. For some, modules may be microservices, for others, JAR files or packages, and for yet others, Maven modules or Gradle subprojects. This diversity in definitions complicates discussions about modularization.

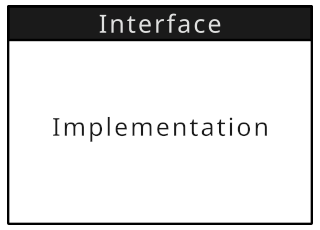

For the purposes of this article, I will adopt a broad definition of a module as a logical unit of code within a program or library, having both an interface and an implementation. The simple concept is illustrated in the image below.

Thus, a module could be, for example, a microservice, a package, a class, or a method. Even a private method is a module living within a class-module. The module’s interface encompasses both formal aspects, such as an API schema (e.g. JSON schema) or method signature, and informal aspects, such as requirements regarding the order of method calls or issues related to thread safe. In other words, an informal interface is one that must be expressed in the form of documentation or comments.

This definition of a module allows us to express its complexity as the sum of the complexity of its interface and implementation. And this complexity is crucial in module design.

Deep and Shallow Modules

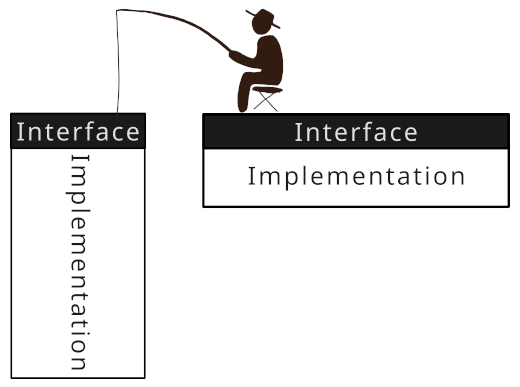

The concept of deep and shallow modules is a significant element in software design. This division refers to how modules are designed and how they present their interfaces to clients. Deep modules feature a small, concise interface that hides a complex implementation behind the scenes. On the other hand, shallow modules have a broad interface behind which lies a very simple implementation.

Deep modules are often preferred. Users can access advanced features through a simple interface without needing to understand all the internal details. In contrast, with shallow modules, the interface may be very extensive, but the provided functionality is relatively simple. In extreme cases, the interface may be more complex than the implementation itself. A simple example could be a method:

public createUser() {

return new User();

}

In this case, calling createUser() is even longer than new User().

The described advantages of deep modules over shallow ones may lead to the conclusion that we should optimize the code for designing maximally deep modules.

However, let’s consider how this affects the extract method or extract class operation.

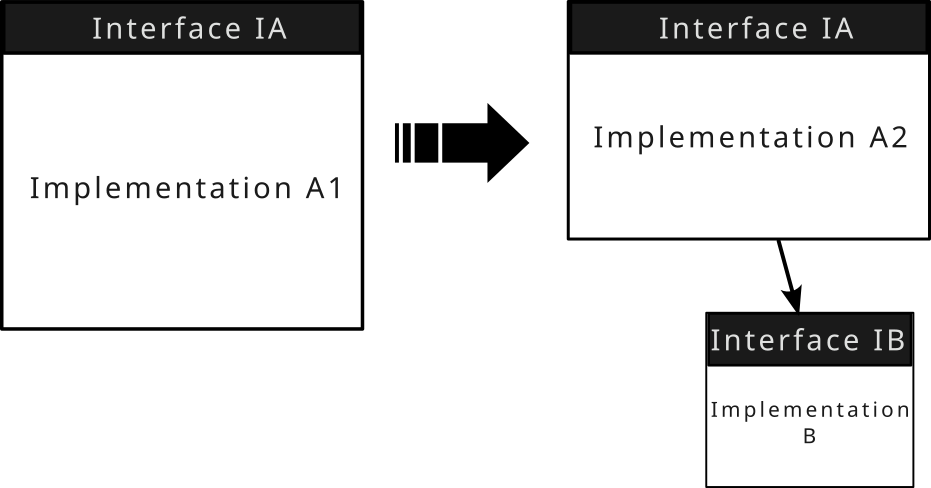

Extract method means creating a new method.

It is a new module that has its implementation and interface.

As shown in the image below, the total implementation before and after splitting remains constant: A1 ~= A2 + B.

However, the total interface is larger IA < IA + IB.

This means that method extraction almost always leads to an increase in the total complexity of the project.

An exception may be when method extraction serves to reduce code duplication, resulting in a decrease in the total implementation.

The increase in total complexity associated with breaking down code into smaller fragments leads to the absurd conclusion that the deepest and simplest design can be achieved when all the code is placed in a single class or method. Undoubtedly, another practice is needed to balance this direction.

The Magical Number Seven

In 1956, George A. Miller, in his article titled “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information”, described how the human mind can consciously process about seven pieces of information at a time.

In the context of deep modules, the magical number seven becomes a key criterion for balancing their complexity, both in depth and width. The complexity of ultra-deep modules can be so great that the human mind cannot grasp them. According to George A. Miller, the human mind can consciously process about seven pieces of information at a time. In other words, interfaces and implementations should not be too extensive or too complicated for a programmer to easily process information, use the module, and modify it as needed.

To clarify, Miller’s research concerns short-term memory and the processing of unrelated concepts. This means that the more we work with a certain code, the better we learn it, and we can start using long-term memory, making room in the highly limited short-term memory. Another issue is the limit on unrelated concepts. For example, if we have seven variables in a method with names that tell us nothing, for many people, this will be the limit of effective use of these variables. Good naming can push this limit up because the name will refer to long-term memory and the relationships between variables. Similarly, adhering to standards, conventions, and patterns can relieve short-term memory. However, regardless of how much we try to stretch psychological studies, human minds have limitations, and it is better not to exceed the threshold of seven concepts within one module.

The principle of seven concepts can also lead to an absurd extreme. By focusing on simplifying individual modules, we can create millions of micro-modules that are trivial and very shallow on their own, but their multitude introduces excessive complexity.

Synergy

From all this, a simple conclusion arises: we cannot optimize only the total complexity of the project because the human mind is not capable of processing such complex issues. A balance is needed between total complexity and local complexity, which naturally leads to the fractal nature of modules.

These two practices balance each other, allowing for the design of optimal modules. Not too large - in accordance with the principle of seven concepts, yet deep enough to be valuable and easy to use. This principle is a good starting point for module design, around which other software design practices can be applied, such as consistency in abstraction levels within the module or consistency in terms of changes.

Fractals in Software Design

Fractals are geometric structures that exhibit self-similarity across different scales. Let’s briefly consider an analogy with a tree drawn by a child. A young child often draws a tree as a green oval on a brown rectangle. However, in reality, the structure of a tree is much more complex; a large branch is composed of smaller ones, each smaller branch resembling the larger one, and so on. Even in the veins of leaves, one can discern a repeating structure similar to the branching of a tree. This analogy demonstrates that the initial view of modules in software may be too simplistic, akin to a child’s drawing of a tree.

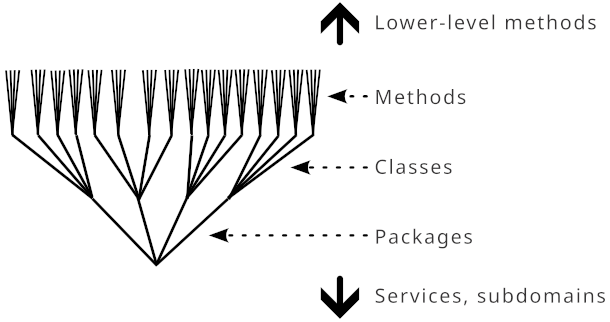

Similarly to a fractal tree, modularization in software unfolds fractally. We start with an Organization, which we divide into subdomains, such as “Product Management”, “Order Management”, or “Customer Support”. Within these areas, there are further services, such as “Payment Processing” or “Shopping Cart Management”. In the case of “Payment Processing”, we may have multiple components handling different payment methods, transaction tracking, or analytics and reports. Depending on the architecture and complexity, each of these components may be a separate microservice, a JAR file, or simply a package. We can continue to delve deeper, reaching methods calling other methods, and so on.

In this approach, we cannot speak of an absolute size for the ideal module. Instead, modularization is multi-level; at each level, we should maintain a balance of depth and complexity limited by the cognitive capabilities of the human brain.

Message for Today

- Deep modules and fractal modularization are important, but they are just a starting point for good design.

- Code should be understandable even for a tired programmer.